Dester was the guide, but T’Charrn walked first across the marshes, never looking back.

It was early morning. The air smelled fresh and damp, with the old complex scent of the marshes underneath it. The sky was grey all over, but shining with a bright diffuse light that seemed to come from nowhere.

Dester’s ears and nose twitched as he tramped along. He knew the outskirts about as well as anyone could. It was a good place for meetings. Meetings with people you might not want to be seen shaking hands with in the town square.

If T’Charrn said he had business here, or past here, Dester could only try to believe him. Sterling, solid T’Charrn, with his thousands of golden feathers. Dester had known him for years, had shared many meals and drinks and secrets with him– but could he say that they were friends?

Dester liked T’Charrrn– loved him, even, at least enough to worry about him. To agree to risk his own highly prized safety on this excursion, a major sacrifice for someone from Dester’s family.

But when he looked at T’Charrn’s wild gold eyes, Dester had no idea what he saw there. Could you really be said to be friends with someone when you didn’t even recognize your own reflection in their eyes?

Where could T’Charrrn be headed? He didn’t walk too fast, but at such a steady clip that it was hard to keep up. Particularly if you took a second to look around. And Dester was always looking, always scanning the path before him and behind him, with both his eyes and both his ears.

T’Charrn entered the huge clump of reeds that marked the outer border of the marshes. The reeds grew irregularly, some small enough to tread on, some arching far over T’Charrn’s head as he disappeared into them.

“Be careful!” Dester called ahead. His voice sounded bright and clear in the morning air.

“It’s all right,” T’Charrn called back. His head had already disappeared behind the reeds, only his soft voice drifting back.

Cursing, Dester followed. The reeds itched and scraped as they brushed against him like a million paper cuts. His galoshes squished and squeaked in the mud.

T’Charrn could barely be seen. Dester twisted his right ear in T’Charrn’s direction, pointed his left ear in the direction of possible dangers behind him, and took a bold step forward.

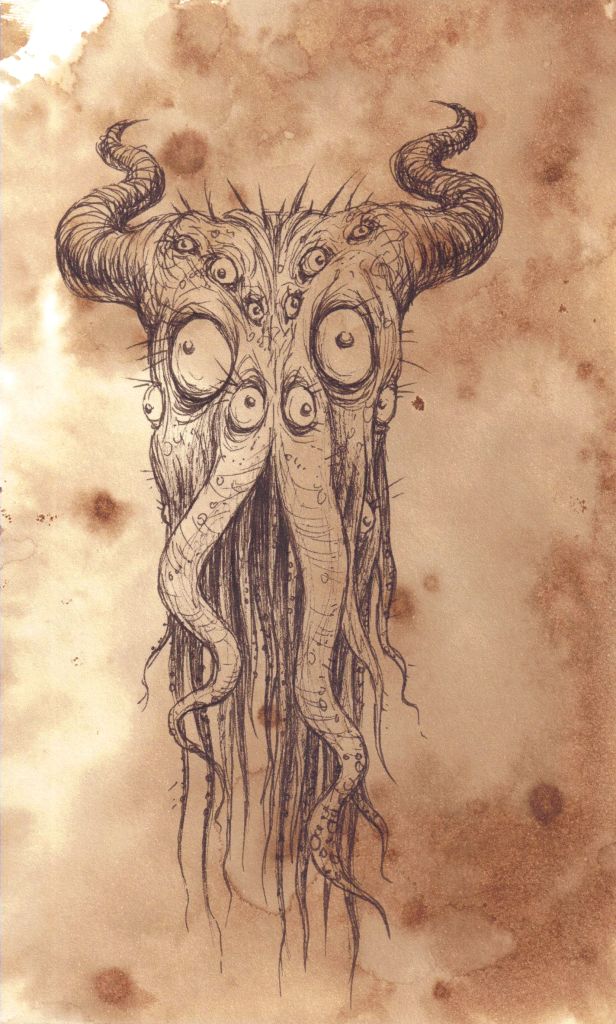

Too bold. Cold fingers grabbed Dester’s ankle in an unbreakable grip. He had encountered a reedmaid.

He struggled, cursing himself for his recklessness, as the tall clump of reeds before him tore itself from the ground, revealing the reedmaid’s powerful form. She dragged Dester to her by his ankle, thumping the ground with her other arm to call her dreadful sisters.

“Let me go!” Dester begged, but of course she couldn’t reply. Faced with the inevitable, Dester froze. Not moving a muscle even to twitch his nose, eyes open but unfocused, he was barely aware of his surroundings.

There was a bright flash of light that Dester seemed to feel as well as see. A clear popping sound came with it, and a sudden faint charred smell, like something burning in the distance. Cautiously, Dester opened his eyes, which seemed to have closed without his permission.

There was no sign of the reedmaid. And Dester looked for a long time. There was no sign of T’Charrn either. The air was very still.

Not knowing what else to do, Dester dusted himself off and walked carefully through the rest of the patch.

On the other side, where marsh gave way to woods, he found T’Charrn.

“How–” Dester began, but stopped. He felt suddenly careful around his old friend. T’Charrn’s quick, darting gaze was the same as ever. His little golden feathers were perfectly aligned.

T’Charrn said, “Do you know these woods too?”

Where the marshes ended to the southwest, the town was bordered by a small green wood, seldom visited, that functioned as a border to the ancient forest that lay beyond town and outskirts alike.

Dester had had occasion to venture into the woods, though for no good reason that he could give.

“Yeah,” he said. “I know them ok.”

*

Dester knew the woods, but T’Charrn walked first, never looking back.

The sun had come out a little, shining through the branches and bringing out the bright green of the woods. Birds chirped. Chipmunks chased each other up trees and around vernal pools.

Old leaves and bark crunched beneath Dester’s feet. Ahead, T’Charrn continued his steady pace.

Dester had just begun to think that they might get out of the woods uneventfully when, through some cursed turn, their path led them past old Tuctutahsse.

He grew from a low branch of an old oak, blocking T’Charrn’s path. There was no clear way past the wide wooden barrier of Tuctutahsse, only identifiable by the old blind eyes that fluttered from the top.

T’Charrn was forced to stop his steady progress. As Dester approached, the slit of a mouth formed, dividing the woody outcropping.

T’Charrn took a half-step back — preparing to do what, Dester had no idea — but Dester stopped him with a gesture.

A creaking voice emerged from the opening. “Well met, travellers,” whispered the creature.

“Honored to meet you, old one,” said Dester. T’Charrn said nothing.

“I’m sorry for stopping you.”

“No trouble,” said Dester. His right ear caught movement behind him. He knew without looking that the wood was surrounding them with barriers from all directions.

“What is your business here?”

For a moment, Dester waiting for T’Charrn to answer. He was both curious and in dread of the answer. But T’Charrn still said nothing.

“Passing through,” said Dester.

“All who pass through these woods must answer my riddles,” the old tree sighed apologetically.

“I understand,” Dester said tightly.

“Why–” Tuctutahsse paused as if for a breath and Dester heard the rustling of leaves– “Why am I?”

Dester’s nose twitched as he pondered the riddle. “Because you are not not?” he tried.

The leaves rustled with annoyance. “Not a play on words,” said old Tuctutahsse. “An answer.”

“You are because the greenwood is.”

The wood groaned as it grew into new positions. Tuctutahsse raised his blind head. “Yes,” he said, “but why is the greenwood?”

“I answered the riddle.”

“But I am still curious.”

Dester looked at T’Charrn for help. T’Charrn was staring out through the trees, but seemed to pull himself together at Dester’s nudge.

“You might as well say why is anything,” T’Charrn said to the old tree. “Why is there something rather than nothing?”

“Yes!” said Tuctutahsse. “You are sensible. That is the question I want answered.”

Dread gathered in the pit of Dester’s stomach. He looked all around him. Barriers and nets of wood covered every gap between trees. They were surrounded — they would never get out.

T’Charrn lay his hand on the gnarled bark of Tuctutahsse. “No one can answer,” he said. “But I will tell you a secret. If you like, you may let us go after you hear it.”

There was no answer, but a round knot formed on the side of Tuctutahsse’s head. T’Charrn leaned close and whispered into it for what seemed like a long time indeed.

When he drew back there was a great gust of wind like an exhalation. The wood relaxed back into the shapes of trees.

T’Charrn continued forward without a glance. Dester could only tramp on afterwards. The ancient forest lay close ahead.

*

Dester had only heard stories of the forest. T’Charrn walked first. Never looking back.

The trees stretched so far upwards that their tops could not be seen. The canopy blocked out the sun.

They walked in silence. The great forest was silent as well.

Dester could not tell how long they walked. The green of the moss and the leaves blurred before his eyes. He began to think that he saw faces out of the corners of his eyes. Pale faces, looking out from the depths of the forest.

Remembering the stories he had heard, Dester called out “Don’t look at the masks!”

His voice rang like a bell in the silent forest. There was no way to tell if T’Charrn had heard, because Dester had fixed the gaze of both eyes firmly on his feet. For the rest of the journey, he did not look up.

*

As they walked, the trees thinned and the ground sloped upwards. To Dester, who had not once looked up since his glimpse of the face of the forest, it was a shock when he raised his head to T’Charrn’s voice and found that he was at the top of a hill.

It was a grassy slope, perfectly comfortable, but far taller than the tops of the trees. Dester could see the forest around them in all directions, enclosing the clearing in which the hill rose. Beyond the forest, in one direction, the smaller trees of the woods, the smudge of the marsh, and there — the town. As small as a child’s toy.

T’Charrn offered Dester some bread and cheese from his pack. They are in silence, looking out over the vista.

“How much farther?” Dester asked when they were done.

“Someone will pick me up from here.” T’Charrn seemed to glance at the sky. “Will you be able to get back?”

“Oh, sure,” said Dester. At least now he knew what to avoid.

T’Charrn was silent and Dester realized it was his cue to leave. He had many questions, but it seemed safest not to ask them — not even to think of them until he was safe at home.

He wanted to say some words of farewell, but no words came to him. He looked back at his home, feeling very much like what he was — a small creature who had seen a glimpse of something outside of his comprehension.

Finally, he turned to face T’Charrrn. They shook hands. Then Dester set off alone down the hill. Never looking back.

by Hannah Baker